Founding Sales The Early Stage Go-to-Market Handbook - Peter Kazanjy

## Metadata

- Author: **Peter Kazanjy**

- Full Title: Founding Sales The Early Stage Go-to-Market Handbook

- Category: #articles

- URL: https://readwise.io/reader/document_raw_content/21449217

## Highlights

- Equally important is identifying the person who has the problem. We’ve already touched on this a little bit, since the person with the problem will often pop up in the problem statement—they’re somewhat hard to separate, and that’s fine. But you should know the players who are navigating, or trying to manage, the business hassles you’re tackling. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jg1y4wkkf8jp0mt66710pnjr))

- Great, now you do it:

• What is the problem?

• Who has the problem?

• What are the costs associated with the problem?

• How do people currently solve this problem, and how do those solutions fall down?

• What has changed enabling a new solution?

• How does the new solution work?

• How do you know it’s better? (Quantitative, Qualitative) ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01je81h05n1hxb5jqqqkq44mgm))

-  ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jeaah9zd2bx3ywf9x83pbt7a))

- As noted above, there is a particular tempo to enterprise sales’ distinct stages. In this first stage, the goal is to set up a commercial conversation about the prospect’s business pains and how your solution could potentially solve them, a.k.a. a “pitch” or “demo.” The goal at this stage is not to sell the solution. You’re simply “selling” a conversation—the opportunity to learn more, and tell more. The same way that the goal of a first date is not to get married, but rather to get to a second date (assuming there is a

potential fit!). You try to get married on the first date, it’s gonna be an awkward scene. Same with sales. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jectabpdvz776rmkjjy0zed6))

- The pace at which this interest falls off is incredibly rapid. As surfaced in research done by MIT Sloan and InsideSales.com, there is a 100x drop-off in contact rates between leads that are contacted within five minutes of submitting a lead form and thirty minutes. And it’s a 10x drop-off just between five minutes and ten minutes. As you can tell, responding to a qualified lead quickly is pretty darn important. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jg0ydc0xhpg0tenddbg9bavp))

- A more recent approach to inbound capture and response is the rise of chat interfaces. Companies like Drift and Intercom have offerings that allow you to have a pop up on your homepage or product page, which can then amount to a “form fill”, but via a chat interface. The problem with this historically is that

you need a human to staff this chat interface, and if you’re at the point where you don’t have enough inbound volume to merit that, you can mis-set expectation with the prospect when the chat window says “Hey, how can I help?” the prospect answers, and then there’s no response. More modern versions of this, again, like Drift, can follow somewhat of a “mad libs” approach and ask the prospect questions, and then catalog the answers—kind of like a demo request form, one question at a time. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jg0yfn72tcnvf2dp117xqjpq))

- The decision to sell a solution in person, face-to-face with the decision-maker in a conference room, or over the phone with presentation and screen-sharing software is typically based on the complexity of the solution crossed with average deal size. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jg1rqgpw6ts1776rvkjbaqzv))

- I find that the best pitches follow a consistent format. Specifically, they start with quick pleasantries, move into discovery, feature a slide-based presentation followed by a live demo, touch on success proof points, and conclude with pricing and commercial discussion. This format is important because it allows you to build the best case for your solution. You start with pleasantries to build rapport and set the tone for the prospect to share information with you and be receptive to your arguments. Discovery gives you the information you need to make an ROI argument to the prospect. (Or, if it turns out that she doesn’t have the pain point that your organization solves, you can end the call and save both of you time!) Next, you use slides and visuals to make sure the prospect has the proper mental model for understanding the sales narrative you’re delivering, and to prepare her to understand the features you demo. All of which builds up to a compelling argument for spending money on the solution. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jg1tb4fk3eh9xdpwdh175fqr))

- The second epoch comes only after you’ve passed the first (importantly, for reasons we’ll discuss more in depth later). This is when you know your solution is viable, solves customer pain, for which they are willing to pay money, and now it’s simply a question of scaling the number of humans who are doing the selling, and, by extension scaling all inputs and outputs associated with that activity. This book will be split accordingly, with the first part coming firs ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwyc6ab9nse1rezt27p72yem))

- Second, in addition to doing the actual work, yourself, a lot of that work will be activity that “doesn’t scale.” Like doing on-site sales visits for a product that will end up selling for less than $1,000 a year. The economics of that would never work at scale. Or manual implementation and professional services for early customers. Or manual lead generation via mindless copying and pasting from one tab of your browser to a spreadsheet in the other. Things like these are not scalable, but at this stage, it doesn’t matter. Y Combinator’s Paul Graham has popularized this notion with regards to consumer products, and it applies here as well. At this stage, this is largely an exercise in information gathering, and as such, is an investment exercise, as much as a revenue-generating exercise. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwycmbjrk3272m5n36wb9qpp))

- Reject a mindset of scarcity—and, hence, hoarding—and embrace a mindset of plenty. The thinking should be "Even if this one does not work out, there’s a line of thousands standing behind it that I need to get to." So if a deal is stalling, if the customer doesn’t have the budget, if it turns out an account is not a perfect fit, and so on, great, fine, close it out. On to the next. You’ll get them the next time around ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwye6ekebmtsdf3qme9vsmmz))

- You should be ruthless with respect to truncating unproductive conversations with marginal opportunities, especially at the earliest of stages, when the world is a greenfield of untouched accounts in front of you.

If you do not, those marginal, crappy opportunities will cruft up your pipeline, hiding the golden opportunities on which you should be spending your time. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01je5cd0evtchx03shhhrdkrgt))

- Everyone’s a fan of working “smarter, not harder” in the modern knowledge-worker economy. Well, sometimes you just have to grind. Sales, like recruiting, is all about activity and leverage. Generally speaking, activity in equals value out. There are certainly ways to ensure that your activity is high quality; you can also lever it with technology to get more in less time, and higher impact out of each unit of activity. We’ll dig into that more later. But to quote Joseph Stalin (likely apocryphally), “quantity has a quality all its own,” and internalizing that is key. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwyejckk0zj04namgdthq2ss))

- More time on the phone. More demos. More proposals sent. More emails sent. More dials. More keystrokes. All of the above is activity, and activity is the goal. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwyekh08sbg3h50qnsfsztqw))

- No more. Just as you need to shift your mindset from scarcity to plenty, the reality is that in order to move opportunities down the pipeline and close deals, activity is job one. Jump first, prepare midair. Template all communication. Drive activity, and output will follow. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01je5chtwsj6e1x6e8cf774e8c))

- The thought should be “Why am I not on the phone?” or “Why am I not sending emails right now? ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwyerdgx4jktwrrcqqgqwg3b))

- Society often gets along through polite obfuscation. Through indirection. Through politesse, and circuitousness. Not in sales land, friend.

Much of sales is about getting down to brass tacks. Do you have the problem I’m trying to solve? Are you in agreement that it needs a solution? Are you prepared to spend money to solve it? ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwyh1yde707d8eq7pnxtckhf))

- Approach your sales conversations with the stance that the prospect will inevitably be a customer. This is more applicable when you’re at the scaling stage, when it is now clear that the solution that you’re presenting has product/market fit. But it can be helpful even at the earlier stages of your go-to-market period. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwz2w4e732cehtbhr9tdp9ng))

- This is not to say that you should not learn from those losses; the reason for the loss should be recorded to benefit product iteration, and also for reference the next time you engage with the account. Be intellectually honest about where the loss came from. Was it timing? Did you get beaten by a competitor because you didn’t follow up appropriately? Or because the product had a feature deficit? And make sure that the answer gets shared with others, so they don’t have to learn the same hard lesson you did by eating a loss. But after honestly reviewing and recording the loss cause, put it aside and move on. You should still expect to win the next one. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwz3qvy7016q0cwgk87j83pb))

- As such, expertness in the vertical in which you are selling is an absolute requirement. You need to be a student of the game you are playing and, ideally, even more expert than the prospects to whom you are selling. This means absorbing as much information as possible about the field, the business processes that exist within it, the common organizational players, and the other solutions that already help with these business processes, or compete with yours. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hwzcp354ef47y1rm5gy4sm5q))

- When people think about what is needed for sales success, they jump to a lot of “right brain” activities. Storytelling, persuasion, rapport building, and such. Socialization, drinking, and dinner. Shooting from the hip and making it up as you go. They don’t consider, or at least not as much, that sales is something that involves lots of metrics, math, and reporting. Guess what? You can’t escape math in sales either— especially if you want to have success at any amount of scale greater than a single rep. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1bxvhp1ewhacmvf1ks94ga))

- Sales in the movies may be about dinners, suits, and booze, and there’s certainly still a steak-dinner component to it. But all of that activity is underpinned by a healthy helping of metrical excellence. You won’t be able to avoid it, so you might as well start getting cozy with it. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1c4jhsg7qwdzs56cg8m4y8))

- Or if you expect to win, are unfazed by loss, and have adopted the mindset of expertise, it’s easier to adopt a stance of inevitability. That, in turn, will help you be fearless and authoritative in your interactions, and more consultative, which will lead to higher close rates. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1cd7gwhaccc47qgzkcjsnh))

- f you expect that you will have high volumes of shallow relationships, you will be prepared to be more direct and efficient in surfacing relevant business details. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1ceer5sx17v4few2cwxrtc))

- While there are a variety of ways to construct your customer-facing narrative, for early-stage, newtechnology sales organizations, I'm a fan of the "problem-solution-specifics" narrative framing.

That is, identify the problem, who has it, how it is currently solved (or not), and why that’s unsatisfactory, followed by what has changed to make this problem solvable in a new way, what that means for the problem in question, how your new solution works to solve this problem, and what the quantitative and qualitative proof points are that validate this line of argumentation. Those will be the core components of a sales narrative, along with potential additions, like competitive messaging (why is your proposed approach better than other proposed approaches?), and all manner of embellishments (like digging into the specifics and features of your solution). ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1dev3k1mqj8jgwtegk6mc1))

- Framing your narrative in this way will also be helpful as you develop your marketing collateral, in that each part builds on the part before. Think of it as an inductive approach: If someone disagrees with your framing of the problem, great, it’s the first thing you’ve discussed; you can focus on that (or end the interaction), rather than rehearsing other parts of your pitch that are not relevant. Or if the person you’re talking to agrees that this problem exists, but not that he has it, again, great; you can save time by not pitching someone who doesn’t care. Narrative framing nicely complements the efficiency mindset that should pervade sales, as covered previously in Chapter 1 on Sales Mindset Changes. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1dk06mzgnxdgh84eaj1rk7))

- You need to identify the business pain you’re seeking to solve, as crisply as possible, so your audience can quickly evaluate whether what you’re talking about is relevant to them. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1wcw4yqr80f3npy9pbxkv3))

- Or in the case of, say, Groupon, it might be “Finding new customers for your local business is hard. With all the time you spend running day-to-day operations, who has time to figure out how to drive new business through the door? But if you don’t grow your customer base to find new, repeat customers, how can you get off the hamster wheel and grow your business?”

Or in the case of Salesforce, it might be “B2B sales is hard. You’re working on a million things at once, and it can be really easy to lose track of deals and let things fall through the cracks, which hurts your ability to reach your quota. And as a manager, it’s hard to know if your teams are working on the right things, if their efforts are directed toward the highest-value opportunities, and how they’re tracking against their goals. Which leads to underperforming teams and missed forecasts.”

Or in the case of HubSpot, it might be “Being an online marketer is hard. Sales wants more leads. And there are so many things you could be spending your time on, but you’re constantly pulled in lots of directions, many of them not particularly fruitful. Really, you just want an all-in-one solution that can help you do the right things, automatedly, and help you keep track of your success. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx1wpcn72zx3g51gyd26s998))

- Understanding the costs associated with the problem you’re addressing will help you frame an argument for why would-be customers should expend budget on your solution. Depending on your space, you might be looking at what it costs to solve a given problem—or what it will cost not to solve it. Either way, you’ll want to calculate the return on investment (the mythical “ROI”) associated with your solution. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx20em04w8x0w7z3w694rs99))

- Or in the case of sales automation and efficiency software, an opportunity cost would be incremental deals missed in a given time frame due to insufficient rep efficiency. For instance, your solution might allow reps to do more in a given amount of time—if instead of closing eight deals of average deal value $8,000 every month, they can instead close ten deals, that’s a 25% bump and $16,000 in incremental revenue per rep per month. In this case, you’re identifying the opportunity cost of not employing your solution. These benefits can sometimes be harder to prove, in that other actions must occur in order to realize the promised benefit. As such, they are sometimes referred to as “soft ROI.” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx20myk71p3rct2185gm9drs))

- Knowing the current solution paths for your problem will be important, in that the thrust of your sales conversations will be to persuade your would-be customers that the means by which they currently solve the problem—or their continued non-solution of the problem—is insufficient for their business, and that they should be implementing your solution instead. You’ll have a hard time driving that argument, or even identifying the current state of the world within a target organization, if you’re not clear on the typical solution paths and their shortfalls. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx2zbwk4rpfq7dzb1gz0p047))

- In high-technology, innovative solution sales, where your solution is brand-new, one of the most common answers to this question will be “we don’t solve this problem.” Your challenge, then, is to persuade prospective customers that it’s worth solving—in that the current non-solution is costly, whether that means actual hard cost or softer opportunity cost. Hence the importance of understanding and being able to model the costs of non-solution. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx2zg2q50kjyv9v24a1m2jg4))

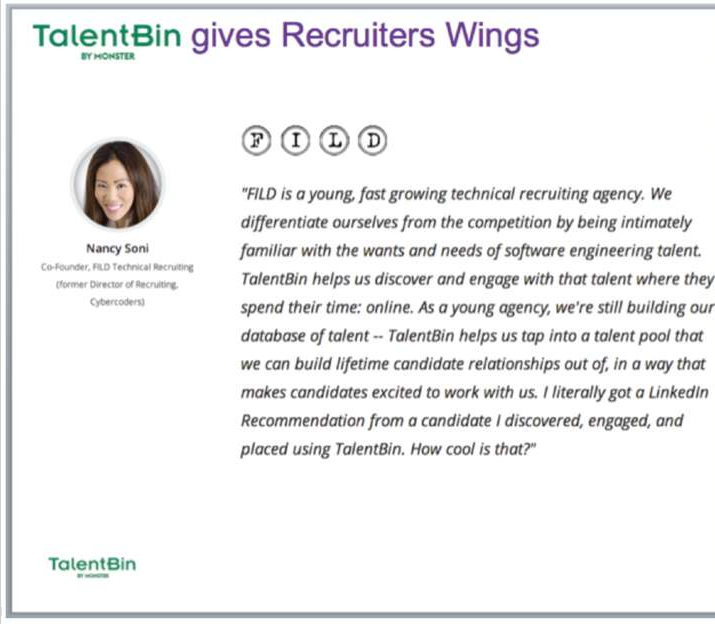

- A step beyond organizations that have implemented processes to resolve their business pains would be those doing so with service providers. For instance, rather than subscribing to a media database like Cision to help their PR team keep tabs on relevant journalists, an organization might just have a PR firm on retainer. Or instead of solving their engineering-hiring problems with process or products, an organization might just work with a recruiting agency.

Solving a business pain with a professional service could be a totally viable solution for the organization in question, but it will have downsides. Cost will typically be one of those downsides, in that service providers need to make a margin for their businesses to be successful. For instance, in technical recruiting, a recruiting agency will typically make a fee of 25% of the first-year salary for an engineer that they place. If an engineer is making $150,000, that’s a $37,500 fee—not a small amount. If an organization has recruiters in place, then a solution that provides them candidate access and engagement tools, like TalentBin, could help them hire the same quality of engineer, but at a dramatically reduced cost—the cost of the solution in question, plus the salary expense of the in-house recruiter. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx2zw0cxp3x3gerbjd4mvgx1))

- Lastly, we have the most advanced organizations, those that already are using products to solve the problem in question. These products won’t necessarily be pure “competition”—they might simply be in the same general space as yours—but this introduces a larger concept that includes competition. That is, these organizations are using solutions that are competing for the budget and user time you want. But that’s often a good sign when you’re qualifying an account (more on this later), since the organization has sufficient conviction in the importance of the problem that they expend budget on tooling to solve it.

For instance, while TalentBin is a talent search engine with advanced recruiting CRM features, with pure competitors in the market, there are a variety of other solutions that organizations use to solve the business problem of engineering recruiting: job postings on a traditional job board, subscriptions to a traditional resume database, or the business solutions of professional networks like LinkedIn. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx2zx5vetxj2kgy7vyjgf5hd))

- This is where things can get complicated, in that the more mature a space, the more variety or alternative solutions there may be—including those that are perhaps not pure market substitutes, but instead are complementary/co-operative solutions. I’m a fan of sales professionals being “students of the game.” The more you know about these other solutions and their relative plusses and minuses, the better. But there will invariably be diminishing returns in knowing everything about every potential solution under the sun; having intimacy with at least the most common ones should suffice, so you’re rarely surprised in a conversation. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx32g6bht4b86kfczp9gy7hz))

- Knowing what has changed will not only allow you to pose a credible narrative, but will also point to the trends you can expect in the market. Pay close attention to those trends and what they mean for your sales narrative—whether they support it or undermine it. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx32qp8my5wcq6azexp3ea6v))

- For Salesforce, this would be something like “It’s like your traditional CRMs, but it takes advantage of the browser and the web to let you access your CRM whenever you want, wherever you are. And it’s way less clunky, and always has the most up-to-date features.” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3cdgx31e6ccasjqada72x6))

- Or for Groupon, it might be “We have acquired email lists of tens of thousands of would-be customers in a given geography, who we’ll help you access by offering compelling coupon-like deals, once a day, that get them in your door.” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3cdkbb8mabpknewekkg5ce))

- As you can see, each part of the narrative builds on the part before. This will be true for every piece of marketing collateral you produce—messaging, email and web copy, slide decks, and so on. And once you’ve covered “this is what has changed” and “this is how we take advantage of that change,” you’ll naturally want to get to “and here’s why we know our solution is better.” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3qbc58a9bhwz6aq8710c0v))

- Because you are now intimate with the problem space, the costs associated with the problem, and the means by which the problem is typically solved, quantitative comparisons should be easy. You already know the general metrics by which existing solutions are measured. Take another look at how you answered “What are the costs associated with the problem?” Now it’s time to present why your solution does a better job, as measured in the same language as existing solutions. Typically, it’ll be as simple as “Our offering does more X” or “Our offering requires less Y.” What that X and Y are will depend on the space, but that will typically be the formula. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3ck9w12e86hzz8zn22e8xg))

- You can also spotlight qualitative differences between your solution and the competition, but this should be in supplement, where possible, to metric-based comparison. And ideally you should have metrical backing to support those qualitative differences. For instance, if you were presenting a mobile CRM offering that promised better usability than desktop CRMs (a qualitative claim), ideally you would have metrics to support those claims. Logins per day or data-quality metrics, for example, could help prove that as a result of this enhanced usability, actions that can be counted—and compared—are happening more or less often than with existing solutions. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3q9sm3p5k4q2ey13twqpf1))

- Pricing is a funny thing. It could be considered part of your narrative, or it could be considered part of your sales materials. In a way, it’s the conclusion of the narrative arc for your solution: “And because of all this, you should pay us this for the right to access our solution.” While pricing is something that is likely to change—usually going up as you gain more functionality, or getting more nuanced as you segment your solution—it’s definitely something that you’ll want to have nailed down, at least in an initial version, when you start having sales conversations. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3qfqp3kaxcndhfhyg307wq))

- I like to approach pricing in an iterative capacity, biasing toward giving away more value than is captured—at least to start. The goal here being that, early on, you want to get customers in the product, using it and testing your value promises; if your solution is priced to perfection, it will likely hurt your close rates and make acquiring those customers more challenging at the margin. This doesn’t mean that you’ll stick with lowish pricing forever. Rather, as you progress, with each incremental conversation, you’ll be getting more information about how the market reacts to your pricing. If you present your product for $100 per seat per month, and no one bats an eye, well, maybe next time make it $150! At TalentBin we started out asking for $99 a month just to test the water, then moved that to $199, $299, $399, and then $499 a month, with an annual contract, paid up front. But we pushed this up over time (not to mention, the product was getting better by leaps as we went). ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3qrfrwxqezdssmtx5w7xzt))

- Another, more advanced, way to do pricing is known as “ROI pricing.” That is, determining the amount of value you expect to provide for the prospect and setting your price to capture some of that value. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3sa1syx9z9s8pcg3wbdty6))

- Another approach to pricing is an extension of this ROI-based mindset—that is, aligning your pricing to the value provided to the prospect. For instance, this might be something like the model that Dropbox or Box use, where the more storage you use, the more it costs. Or you might approach it like Marketo, Eloqua, Act-On, or HubSpot, where the more contacts you are drip marketing to, the more the solution costs. This structure has the advantage of allowing a customer to “start small” (either with a small portion of their total demand, or because their total demand just isn’t that large), and then grow— ensuring that the price you capture from them grows in step with the value they’re deriving from the solution. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3sm1qgd383fqktd9g4zkjp))

- We touched on this above, but you want to be careful about “pricing to perfection.” That is, watch out for charging such a high price that all the stars have to align for the prospect to get a sufficient amount of value out of your solution to be satisfied—or, before then, for the prospect to even believe that they could get the requisite value. On the one hand, you don’t want to give your product away, but pricing too high will work against you in a number of ways. First, it will hurt your win rates. A prospect can totally be on board with the pain you’re solving and believe that you will solve it for them, but if you are charging so much that they don’t believe that the ratio of pain solved to money paid is in balance, they won’t buy. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx3snejfth114cykjxfd19de))

- What is the problem? Who has the problem? What are the costs associated with the problem? How do people currently solve this problem, and how do those solutions fall down? What has changed enabling a new solution? How does the new solution work? How do you know it’s better? (Quantitative, Qualitative) ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx4kavjpte7d2q0wja75n5fj))

- At a bare minimum, you should structure your sales deck to correspond to the various steps in your sales narrative ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx4m9t4x63decwa96mfxj13k))

- Now that you have your materials pulled together and are ready to engage with some prospects, you need some prospects to engage with! And that means prospecting, going out and looking for some relevant potential customers. Later on we’ll be talking about how to do this at scale, and we’ll also be covering how to get prospects to come to you—what’s known as “inbound marketing,” which has been heavily popularized by folks like HubSpot. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxbb9dbsrr9sczhwqrcf1a5s))

- And while it might seem attractive to go elephant hunting, given that those deals could be potentially the largest, you’ll want to think twice there. Large organizations have existing legacy systems and workflow and are less reactive; even if you do end up closing them, you may have trouble onboarding them and supporting them effectively. And if a single elephant ends up being a disproportionate amount of your revenue, you may end up beholden to them to build features that they demand. You might end up a professional services company for this particular elephant. The elephant might fall and crush you just as you’re doing your victory dance. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6n27ehpfmhx27pxbse79bv))

- Similarly, rabbits might seem attractive, in that you can get buy-in from a senior decision-maker quickly, and there won’t be a lot of legacy process they need to modify to adopt your solution. Unfortunately, the size of their deals may not be much to write home about. And the lack of business process may mean that they aren’t all that good at doing the thing your solution enables, which means that they’re more likely to churn out. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6n2whmmha2azc0mwbjymvm))

- Targeting “deer” is usually a good initial approach. They’re large enough to have a goodly amount of the business pain—sufficient to entertain a new solution—and likely have business processes that can ingest new technologies. But they’re small enough that they can make purchasing decisions quickly, and their existing business systems are probably not so entrenched that adopting a new solution would require substantial change management. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6n2zahw8675wmqj3t94q3m))

- There’s a concept of “complementary” decision-makers as well, who are typically internal customers of the primary decision-maker you’re seeking to target. That is, while the VP of Talent is the person responsible for solving the business pain of “hiring more engineers,” it is the VP of Engineering, or CTO, that has the downstream business pain of “ship more software.” Or even though it might be the Director of Sales Operations who is responsible for making sales reps more effective, ultimately it falls to the VP of Sales to generate more revenue. That CTO or VP of Sales definitely has a stake in solving the business pain you’re looking to address. Sometimes you can target these complementary decision-makers, with the intent of being referred to the appropriate primary decision-maker. You might even engage with these complementary decision-makers to make the case for your solution and, having convinced them, join forces with them to convince their colleagues, together. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6mpp8qvyszh6nw8sf2xnft))

- I like to think of the sales cycle bucketed into several major stages: First, there’s “outreach and engagement,” where you’re engaging a prospect account with the goal of setting an appointment. Next comes “pitching,” where you begin a commercial conversation with a prospect with the goal of eliciting more information about the particulars of their situation and persuading them that your solution fits their pain. And the stages continue all the way to “closing,” getting the prospect to sign on the line that is dotted, and the associated pipeline management. Each stage has it own set of actions, and it own goals, which we’ll cover in depth. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6fykg6nx983ea48vgkcwaf))

- As noted above, there is a particular tempo to enterprise sales’ distinct stages. In this first stage, the goal is to set up a commercial conversation about the prospect’s business pains and how your solution could potentially solve them, a.k.a. a “pitch” or “demo.” The goal at this stage is not to sell the solution. You’re simply “selling” a conversation—the opportunity to learn more, and tell more. The same way that the goal of a first date is not to get married, but rather to get to a second date (assuming there is a potential fit!). You try to get married on the first date, it’s gonna be an awkward scene. Same with sales. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6fwerdg2a0445q0jg0qw15))

- The success of your phone outreach will often be contingent on the times at which you call. Connect rates can vary substantially depending on the day-in, day-out tempo of your prospects, so being in tune with this is helpful. For instance, if you’re calling on white-collar office workers (say you’re a recruiting or sales solution and are calling on Directors of Sales Operations or VPs of Talent Acquisition), then your better bets are going to be early in the morning, just as people are getting into the office, or at the end of the day. Middle of the day is tougher because people are away from their desks, in meetings, and going to or coming from lunch. Another trick can be particularly late calling. If you want to avoid gatekeepers, and get directly to a senior executive, often they are still around at 6pm or 7pm, when executive assistants have gone home. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx61kc4egqbm5zp09nhww8q2))

- Your best approach here is to use very, very simple statements of the value of your product, so someone who isn’t necessarily invested with authority can quickly parse them and realize, “Hey, it’s probably a good thing if I let Bob know about this.” (For example, if you’re Groupon, you might say, “Hi there! I’d like to be in touch with the owner, because I’d like to discuss how Groupon can make him twenty thousand dollars in one day. Who’s the right person to talk to?”) The goal is to make it clear to the gatekeeper that by helping you engage with the right person, he will be looked upon as a hero by the eventual decisionmaker, likely his superior—and that if he doesn’t, that same superior will be upset to have missed this opportunity. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx698e2tbp8ae6ny45c89xzf))

- There are other sneaky approaches to voice mail, like not actually leaving much context, and instead saying something along the lines of “Hey, Frank, this is Pete. Call me back. 650-892-4475.” Or even skeezier, “Hey, this is Pete returning your call. Call me back at 650-892-4475.” (That last one is like adding a fake “Re:” prefix on emails, to trick the prospect into thinking he’s already participating in a back-and-forth). While this sort of thing can be employed by market development staff, it’s a little more advanced than you probably need to implement. Instead, the straightforward voice mail, patterned after your outreach emails, is probably your best bet. And importantly, always use voice mail in conjunction with email; if your voice mail is well formed, and well delivered, it may inspire your prospect to simply hit “reply” on the email that came in at the same time. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx69p1gba7f79wgns5g80e82))

- If you follow the prospecting and messaging instruction we’ve already covered, the amount of out-andout rejection you encounter shouldn’t be terribly high. Prospects don’t like to completely close the door on something, but rather prefer the “not now” approach to forestalling decision-making (even if it’s the tiny decision of putting a meeting on the calendar!). ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6abr7k8a99vp0s3mwf8kp5))

- Firstly, you shouldn’t take rejections as “never,” but rather as “not now.” If you think about every massive company out there, the Salesforces, LinkedIns, and others, there were thousands of prospects who rejected initial outreach and eventually became happy customers. When you encounter out-andout aggressive rejection, treat it as an opportunity to make sure your goal is understood and give the prospect another chance to soften: “Okay, I understand. It sounds like this is something that might not be a priority right now. My only goal was to seek to understand your business pain ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hx6ajctk4f3k9zqerx9xpad3))

- At bottom, pitching is the process of commercial persuasion, ending in a sale. Appointment setting was about persuading the prospect that this solution could potentially help with her business pains. Pitching is about persuading her, and other stakeholders in her organization, not only that they have this business pain, but that it is of large enough magnitude that it must be solved, that your solution will indeed solve it, and that they will be able to capture value—“return on investment” in the nomenclature—by implementing your solution.

Moreover, pitching is about persuading the prospect that she needs to deal with this now, rather than later. That the opportunity cost of holding off is too high to bear. And that notwithstanding the various pains facing her organization—and there are always many things that can be fixed—it’s worth the money and time to implement your solution, ahead of all those other things. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxew54hy1thz21fz1djvtjjz))

- Potential Value x Value Comprehension x Belief = Likelihood and Magnitude of Sale ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxew934bh966b1zk4g1qq42y))

- Did you know your presentation starts before you even get on the call or show up at the prospect’s office? Just as professional athletes use scouting reports and watch previous game recordings to maximize their performance on game day, the best sales staff rigorously prep for their demos and presentations to ensure they make the most out of them. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxf9r8cwcbzmgxeegrf9d2gj))

- Lastly, while business pain and stakeholder research is paramount from a nuts-and-bolts standpoint, you’ll want to take time to gather conversational guides, icebreakers, and rapport-building information for the first couple minutes of your call. If you think blathering about the weather is going to get this done, you’re really missing out. That’s the limp fallback of someone who doesn’t do his research ahead of time. This is especially important for phone sales. In face-to-face meetings, it’s somehow easier to establish rapport. You have to be intentional about it on the phone, though, so selecting a piece of information you’re going to key off of is all the more important. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxsn76k1hj7m1jee4kqs5gex))

- As you do many of these presentations, your approach will evolve and you’ll eventually form a pre-call planning checklist, along with a discovery question checklist. When you do, capture this information in your CRM. You’ll be having dozens of these presentations, and when you go to follow up with the prospect, much of the pre-call research is reusable. Capturing it in its distilled form saves you time.

Better yet, you’ll be creating a piece of tooling for the sales reps you eventually hire to scale your activities. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4n13m88cz7tb6km5zbnm3))

- Tags: #sales

- Once you have all of this information, you should be able to form a plan and establish your goal for the call. If you’re talking to the right decision-maker, and it’s clear that the account has tons of need for your solution and spends lots of money on analogous products, maybe that goal is to win consideration of a purchase. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4nj9wjswc0n3v7wrn8dp3))

- I find that the best pitches follow a consistent format. Specifically, they start with quick pleasantries, move into discovery, feature a slide-based presentation followed by a live demo, touch on success proof points, and conclude with pricing and commercial discussion. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4r9bw1k63k522n3fb4177))

- First up are end users. They are going to care about making their jobs easier, pleasing their internal customers, making themselves look good to their managers, and setting themselves up for career progress. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4yckefa669jjwrs7mja5f))

- Next you have first-line managers. They’re going to be more interested in the ROI arguments you bring to the table. They’ll be mindful of the impact your solution has on their commitments to internal customers. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4y6wbad3nwygm9kt5mq3k))

- Lastly, there’s the second-level managers or CXOs. They’re going to be responsive to arguments that drive top-line business value for the entire organization. For instance, if your solution speeds onboarding of new salespeople, so they can become fully productive quickly, the CEO will care because more salespeople adding more revenue literally raises the value of the company. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk4z3mc2724r2xry4hg6cw3))

- For many people, it’s a big change to adjust to the amount of repetition that goes on in sales presentations. As writers and communicators, we typically worry about saying the same thing more than once, for fear of being boring or insulting the intelligence of the audience. In a sales presentation, repetition is your friend. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk530bc3v80h68nc8hjwc5y))

- If the goal of the presentation is the communication of information that drives a prospect toward a commercial transaction, it’s probably pretty important to know that the information is being consumed!

How do you do this? Validate that your prospects are paying attention, and validate that they’re understanding. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk54wrgfs410mg5g6dpya4t))

- Across the board, the best way to confirm that someone is paying attention, to regain attention if you’ve lost it, and to validate understanding is to ask questions. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk55a1rbkd79zdsfgye3h00))

- The most basic question is “Does that make sense?” But the problem there is that prospects don’t want to look dumb, so this often invites a standard “uh-huh” response, regardless of whether they are following along. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk55wf873m58hk6jh994szp))

- You desperately want prospects to tell you if they’re not following along so you can fix it quickly! One approach I use is proactively giving permission to say, “I’m not understanding.” For instance, when presenting a slide for TalentBin on the growth of new specialty social networks like GitHub, Stack Overflow, Meetup, Behance, and so forth, I would ask, “Have you heard of some of these before?” to validate understanding. But to prevent prospects from saying yes even if they hadn’t, I would say something like “It’s okay if you haven’t. Many are fairly new, and I didn’t even know about them before we started TalentBin!” or “It’s okay if you haven’t. These are pretty dorky specialty sites!” By doing this, you give prospects permission to not know, and ensure that they aren’t too embarrassed to communicate their lack of understanding to you. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk57ns8326xsjxx099sh87p))

- Another approach is to ask a specific question that requires a specific answer, ideally correlated to the pain point, solution, proof point, or feature being discussed. For instance, if you were Immediately, and discussing the challenges of field sales reps documenting customer-facing interactions, rather than saying, “Does that make sense?” the better approach would be something like “Do you find your field reps have this same issue?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk589xy371s0ndx4rmddweh))

- Lastly, you can do open-ended questions as well, like “What questions do you have for me so far?” allowing the prospect to bring up anything that has been bothering her. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk597nt8bgy73pr7wv41y6s))

- One thing you may have noticed in the preceding section is that the questions used to validate attention and comprehension often sound a bit like discovery questions—or at least shortened versions of them.

This is not a coincidence. In fact, as you proceed along your presentation, you can implement a form of “rolling discovery,” where you learn more and more about the prospect’s pain points, existing solutions, and so on, right at the moment that you’re talking about a particular topic. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk5bgf9w8xz4qak7mmqz3wh))

- Extending from repetition and comprehension is the notion of building agreement. That is, at every opportunity, you want to elicit agreement from your prospect that his worldview is aligning with the one that you’re espousing. If you do this well all along, at the conclusion of your pitch the sale should be a no-brainer! At that point, the prospect has agreed with you the whole time, about the pains he feels, the fact that existing solutions are not getting the job done, that it’s important to solve this problem now, and that the solution you’re proposing definitely does so. Now let’s just sign a contract! ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk5n8hgb10vvjd048fr76vk))

- Resist this. In pursuit of comprehension and agreement, you need to make sure that your delivery is methodical. Deliberate pacing will ensure that words aren’t missed and that your prospect has the best chance to comprehend what you’re saying and how it relates to what’s on the screen or projector.

Further, pausing here and there to allow for questions, and to proactively test for comprehension, ensures that there are opportunities for the prospect to “catch her breath” and clarify, if needed. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk5sbcd5q4b2dws8skky8mn))

- A great way to facilitate being on the same page is what are known as “micro-contracts” between you and the prospect. That is, before you do something with the prospect (e.g., ask discovery questions, present slides, demo), you articulate what you want to do and why and ask if she is in agreement that it is the correct next step. This is a tool espoused in Sandler Sales Methodology, called “upfront contracts” there. You likely used it when setting the appointment, when you characterized the agenda and gained the prospect’s agreement to attend, but it extends to the pitch, and even beyond. As you progress through your pitch and your demo, and through incremental demos, negotiations, and implementation, setting clear expectations with the prospect will help keep things moving and prevent getting stuck. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk60c33s80snda20snz4x94))

- For instance, if after your initial demo it appears that the solution is a good fit, but there is a need to involve another decision-maker, then you should “contract” for that next meeting. That is, say, “It seems to me that you believe this solution can help your organization solve <the problem that you’re focused on>, and that you believe it would be a good fit. But in order to progress, we need to involve Jeff so he can validate the conclusion we have come to. Is that right? If so, let’s get another presentation on the calendar for you, him, and me. Do you have your calendar and his available to you?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk606rffkvzkmccpta9ankg))

- At any point in the sales process, if you uphold your side of one of these micro-contracts, but the prospect diverges from his commitment, it is an early warning system. And you’ll be justified in stating your concern: “I’m confused. We agreed that you believed this solution made sense for your organization, and is well positioned to help you save $X per year. Our next step was to meet with your CFO to help him validate your conclusion. But two of those meetings have been canceled at the last minute. Can you confirm for me that this is something that is a priority, and that you believe is important for your organization?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk650p36wvc32mdqbah4724))

- The best way to close out the conversation is to frame it in terms of respect for the prospect’s time. Something like “You know what, <name>, based on everything we just talked about, I don’t think that what we’re up to is going to be super helpful in your <whatever you do> efforts. We mainly help out people and organizations that <fill in the specific thing that your solution solves here>. I know you’re a busy person, and don’t want to waste your time on something that isn’t helpful. I’m happy to send you some slides or demo videos, but I would propose that we just go ahead and conclude this call, and I can give you back thirty minutes of your time. What do you say?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk6aayc7p82y48abys2c6dv))

- If you have, it is extremely important to not skip this step. For founders and first-time salespeople, presenting pricing and affirmatively asking for the sale is often where the most mistakes are made—largely because they don’t do it. After going to all this trouble to find the prospect, make an appointment, and then present the value of their solution, they drop the ball short of full execution.

It’s an understandable error. This is where you can feel the most exposed to rejection. It’s akin to another common founder error, selling to people they know versus qualified accounts because acquaintances are less likely to reject them. But we’re going to surmount this! And we’re going to get good at it. Part of the trick here is convincing yourself that your solution is worth it. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxk6gkkf2ght29pvex6svrt1))

- If a prospect does indeed ask for pricing, you should be happy. People typically only ask if they’re interested in buying, and you just captured a valuable piece of information: this prospect likely thinks your solution makes sense, provided the price is right. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxkf26egwxhyyb84r509jm42))

- If a prospect doesn’t ask for pricing unprompted, I like to use this as an opportunity for a “trial close,” rather than just driving ahead to a pricing slide. That is, I gather more information about his mindset, post-presentation—something along the lines of “Given all we’ve covered, is this something that you see being useful in solving your <fill in problem here> challenges?” If the answer is no, that’s potentially very concerning, since they’re articulating lack of interest without even knowing the price. Yikes. It will be all the more important, in that case, to dig into the prospect’s objections, because this may be indicative of an issue with your prospecting, discovery, presentation, and demo process. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4vxzttyhpj1jgm7k3e9ma))

- When presenting pricing, it’s great to frame it in the context of existing solutions, best alternatives, or opportunity costs that you’ve already touched on in discovery and your presentation. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hydbqhn6tkhwyh6xdnqgt1wc))

- When you’re verbally presenting pricing, you’ll want to start at the most extreme case, knowing that you’ll probably end up being negotiated down. This is why presenting just a single unit of pricing (e.g., one seat, one discrete unit of use) is helpful, because when you then roll that up to the fifty seats that the prospect needs, you’ll have baked in wiggle room for yourself. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxvcrxk79gaqcp8nqa7f2ge3))

- When you have leading indicators of interest, it’s time to proactively ask for the sale. None of this “So, what do you think?” wishy-washy stuff. Forthrightly ask for the business ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxkpk3nj632sv0vded5f43jv))

- so much of business-to-business selling is simply understanding where you stand with your prospect and taking the next appropriate action. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hydc67nf89rfa047qv9968n2))

- But the point is, directly asking for the sale (compared to beating around the bush, or avoiding it because you’re afraid of rejection) is 90% of the battle. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxkpn6bgnpt7farmp9b37ezt))

- “What specifically is blocking us from progressing right now? ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq2pvx64f3qmbjt8387npbt))

- s the authority to make this decision the only thing that is blocking us from getting you started?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq2wqgkn7z13tfhgz9d3z8v))

- Of all the generic objections you’ll get, “We don’t have the need” is the most concerning. As touched on above, if the prospect doesn’t think your solution is a fit, there’s something problematic going on. It goes back to the “persuasion formula” we talked about at the beginning of the chapter. Does the prospect really not have the need, and you just did a poor job on prospecting and discovery? Then you probably shouldn’t be selling to him. Or does he actually have the need, but is not grasping the potential value? Or does he not believe that his organization would capture it? You need to figure out the issue. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq3fbm16ktfk1nwx8f8qm5d))

- “I’m confused. Based on our discussion at the beginning of this call and my research on LinkedIn, your company has fifty outside sales reps. And from what we talked about earlier, your sales management struggles with getting those reps to log meetings, emails, and contact information in the CRM because they’re mobile all day long. Is this not the case?” ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq3r67pykmpckhgjnmy8mhs))

- Often when prospects articulate that they “don’t see the need” or “don’t think it’s a fit,” they’re actually making this objection, in disguise. That is, the prospect validates that she does indeed have the need in question, but articulates to you that she is unwilling to make a change to her way of doing things. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq3t7xwxdywkq2861hdgerc))

- The best way to approach these objections is to take the hidden cost of continuing to do things business as usual, whether true cost or opportunity cost, and make it visible. You may recognize some of this language from the “Proof of a Better Solution” sections of the Sales Narrative or Sales Materials chapters. That’s no coincidence—this is the point at which you should bring out your quantitative and qualitative proof of a better solution. Do the actual math for the prospect on what she’d be missing out on. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq3w3y9t0rahzqa8zpx3ksa))

- This is a variant of “we’re happy with how we do it now,” but a slightly better version. That is, the prospect agrees that his organization has the need, that the solution addresses it better than what they have in place right now, and that they will get value out of progressing with the purchase. And given that he hasn’t just jumped to the king of objections—“no budget”—it would seem that he knows they can pay for it. The sticky part is that they have other things that are higher priority right now. This objection may also appear as its cousin, “timing is bad.”

The reality is that your prospect always has a bunch of competing priorities, including day-to-day execution of his role, so the key to addressing this objection is to reduce the perception that implementing your solution will be a lot of work. That is, the implication here is that he only has so much time to roll out a new solution, and that that time is already spoken for. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq438fhn14gksc9nqtqyjry))

- An objection around price is actually a great place to be. That is, it would appear that the prospect is convinced and wants to do this. Now you’re just haggling over the price.

Pricing objections can mean a couple different things, and it’s important to precisely nail down what the prospect is actually objecting to. That is, sometimes vague price objections amount to posturing for a discount. In that case, you need to just get down to pricing negotiation, rather than a deeper conversation around value provided compared to price. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq44q4vs6jgrajdt3vq4ksh))

- Not having budget is often a failure of imagination on the part of the prospect, and it’s just a question of you helping them find that budget. (That is, unless it’s being used as a red herring for another objection, in which case you still need to get to the real issue.). In Discovery, we talked about qualification using frameworks like BANT and ANUM (where “B” is “budget” and “M” is “money”), and how the challenge with new-technology sales is that there often isn’t an already-existing budget that addresses the solution you’re selling. This challenge will also show up in closing conversations as an objection to be handled.

In discovery and qualification, did you validate that the organization does actually purchase tools for solving business pains, and that the decision-maker that you’re working with has done this before, or

knows that it can be done? If no, well, that was a big boo-boo back then, because they really may have “no budget,” in the sense that they don’t have a process by which to spend money on products to help their business. Yikes. So we’re not going to address that as an “objection,” as that is really a disqualifier—if the organization doesn’t have a notion of spending money to make money, well, we’re not in the business of teaching market capitalism, per se. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4840whm9f1jzzt71bhw7k))

- This is one that will show up frequently, and you need to be careful. The concept of a “trial” is not a bad one. In fact, a demo that is well tailored to the prospect, ideally including his organization’s data, is pretty darn close to a trial. And the notion of a customer reference is a good one too; it is an example of a powerful piece of “proof data.” But you need to use caution here for two reasons: One, the prospect may be using this as a way to avoid saying no or surfacing the actual underlying objection, and simply putting off a decision. And two, you don’t want to lose control of the deal, or add unnecessary time and complication to it. When someone asks for a “trial,” and you just flip them a set of credentials with no structure, you’re simply asking for him to come back at the end of the week and say, “Wow, yeah, I didn’t get to this. Can I have another week?” Let’s make sure this doesn’t happen to you, as it wastes your time, hurts deal momentum, and plants the seed in the user’s head that he may not end up using the product after he buys it (he isn’t using it right now, right?). ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4aqp3qqrxvps6y9e3qw9a))

- Competitive objections can be a really helpful way of proactively framing the conversation around other players in your market. While bringing up competition proactively can be problematic, if the prospect brings it up, you should jump all over it. First, if you already know, based on your discovery questions, that the prospect has a competitor in place, or is considering one, you can take the initiative to address it. Or, if that didn’t arise in discovery, but a question asked later in the pitch indicates that he is thinking about competition, you can run with it. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4c8gn33kajvya9jn6pr24))

- Regardless of the type of objection, whether it’s one of the more generic ones or one that is solutionspecific, the pattern of handling them remains the same. That is, you should “catch” the objection; turn it to the “question under the question”; respond to the objection with quantitative and qualitative arguments that prove the case, supported by visual and textual sales materials; validate understanding of these arguments (“Does that answer your question? Does that make sense?”); and then pick up where you were before that objection. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4dsfyj6hzx6kr6y25qnh5))

- “Negotiation” meant that we were negotiating price, but that all other hurdles had been passed. The relevant stakeholders had bought in, and it was just a question of agreeing on a price and terms.

“Verbal Agreement” meant that the prospect had agreed on a pricing option, and that we needed to send a contract. Things should not have been in this stage for long. But it was useful when an agreement showed up in the rep’s email, and he didn’t have the fifteen minutes to send off a contract just then because it was the weekend and he was away from his laptop, he was about to hop into a demo, and so on.

“Contract Sent” is pretty damn clear, but it meant that those opportunities should be watched like a hawk. The prospect had agreed to a price, we’d sent them a contract to sign, and now it was a matter of crossing our fingers and toes that they signed it. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4jn5y7vq6k66ddw4cn1a1))

- “Closed-Unqualified” was a special case, for opportunities where we should never have done a demo to begin with, because it turned out that the account didn’t have the need for our solution. We would pay close attention to these to figure out what we’d done wrong to end up doing a demo for an account that could never buy—which of course is a terrible waste of sales time, and cause of prospect irritation!

“Qualified” was for opportunities where the demo had been done, and there was some indeterminate next step that wasn’t better captured by any of the other stages (“Seeking Approval,” “Sent Proposal,” etc.), like when the prospect needed to “think about it” or “talk with my team.” This stage usually was a catchment basin of cats and dogs that needed better next steps, and I should have done a better job with specific modeling criteria here. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01hxq4k7qq5t7s9k0qp0j9f3rc))

## New highlights added April 10, 2025 at 4:25 AM

- I don’t want to get too deep into inbound marketing, because when you’re very early in your go-to- market, it’s usually pretty unlikely that people will know who you are, what you do, or that they need you. This is the challenge with selling innovative solutions early on: if no one knows they have the

problem you solve, or that there is a solution like yours that can solve that problem, they’re not going to be Googling for you, or stumbling across your site.

Creating content, like blog posts, tweets, infographics, and such, and making sure that they are well SEO’d to engender inbound leads at scale, is what is known as “inbound marketing.” This is a more advanced form of lead generation that we’ll get into in a later chapter, as it’s typically not appropriate for a very early-stage go-to-market. (You’d be producing a bunch of content for people who aren’t

looking for it…). There can be exceptions where you’re attacking an existing market for cheaper—kind of like Hubspot took the power of marketing automation like Marketo and Eloqua, and brought it to the SMB and mid-market. But I find that these are often the exception, especially when we’re talking about acquiring your first 100 customers.

When you do get more advanced, there are lots of resources to assist with this, not least Mark

[Roberge’s book](http://www.amazon.com/The-Sales-Acceleration-Formula-Technology/dp/1119047072) [The Sales Acceleration Formula](http://www.amazon.com/The-Sales-Acceleration-Formula-Technology/dp/1119047072), chronicling analytics-driven sales powered by a robust inbound marketing machine. It’s no surprise that this come from the former Chief Revenue Officer at Hubspot, the company that has done some of the most impressive work at popularizing inbound marketing as a practice. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jresxnc0e3qr4brhcf223a95))

- In fact, the second thing that people screw up about inbound leads is giving up on them too soon. Again, our friends at InsideSales.com and MIT Sloan figured out that each incremental attempt you make to reach out to an inbound lead adds another 15% chance of contacting them, falling off substantially after the sixth attempt. But after six attempts, you should have had roughly an aggregate 90% chance of making contact. So don’t give up! Remember, they asked for it, so you have nothing to fear. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jretcftdcvr3jgjcwd9rntcy))

- Potential Value x Value Comprehension x Belief = Likelihood and Magnitude of Sale ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01jrete5tf7kz6vj2z52t5essv))

## New highlights added November 21, 2025 at 7:42 AM

-  ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01kakennvsevhqskacqryj9sak))

-  ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01kaker0ens3xzkvyvwvgnjmvw))

- Many companies use a “logos” slide for this purpose. If you go that route, make sure to include

examples of all the segments that you care about. In TalentBin’s case that was small to large business, and both commercial enterprises and staffing agencies. The goal is for the prospect to look at that list and say, “Ah, I see others like me. And I see others whom I aspire to be.” While you might be worried about getting permission to share this information with prospects, when you’re very early, and trying to go from 5 to 50 to 100 customers, you have bigger issues. Just make the slide, share it in live

presentations, but don’t send it via email. Additionally, just bake publicity rights into your Master Service Agreement that customers agree to when they sign a contract. ([View Highlight](https://read.readwise.io/read/01kakeqczvqc0yngr52vg5rjsw))